The research project “I’ve made you a palm-tree” is conducted by visual artist PASHIAS in collaboration with art historian Iosif Hadjikyriakos, centred on the establishment of the palm-tree as a staple feature in Cyprus’ landscape, heritage and identity, investigating historical documents and testimonies from the Phivos Stavrides Foundation, alongside contemporary social and cultural urgencies.

Initiated in 2018, the project begins with the homonymous 24/7 exhibition “I’ve made you a palm-tree” that took place from December 2020 to April 2021, in the form of an urban intervention at former Hondos Centre (20 Zenas Kanther Street, opposite Paul Restaurant) in Nicosia's commercial centre. Activating the building's facade, the passerby - viewer can access all exhibits from the sidewalk, during the whole day and night, according to their own time and spatial comfort, as the only open and functioning exhibition in Cyprus at the moment, due to newly implemented measures against the pandemic. The exhibiton is a joint independent effort by PASHIAS, Iosif Hadjikyriakos and architect Katerina Scoufaridou (Emblem Gallery), supported by Pantelis Pashias Co. Ltd and Nicosia Municipal Arts Centre (NiMAC).

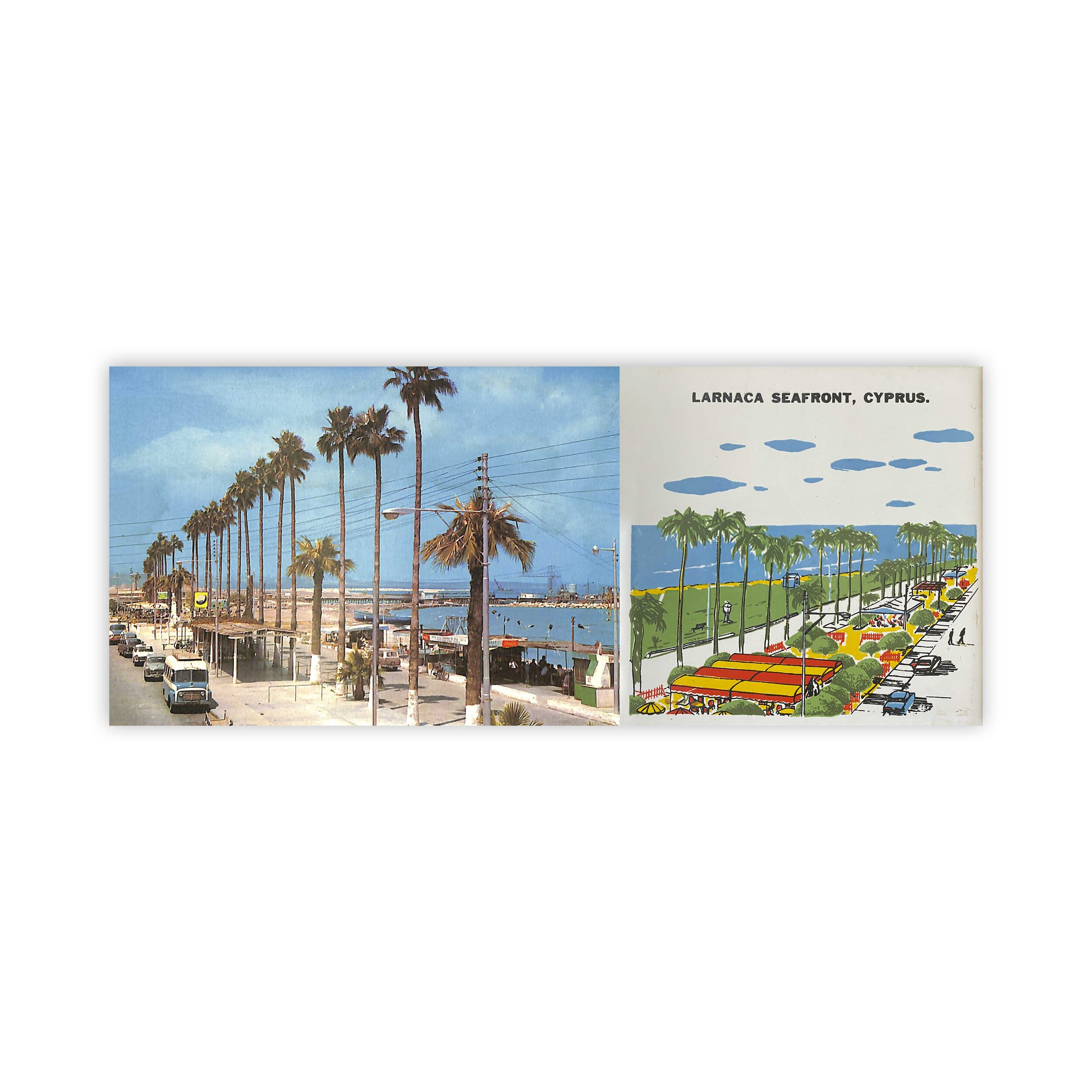

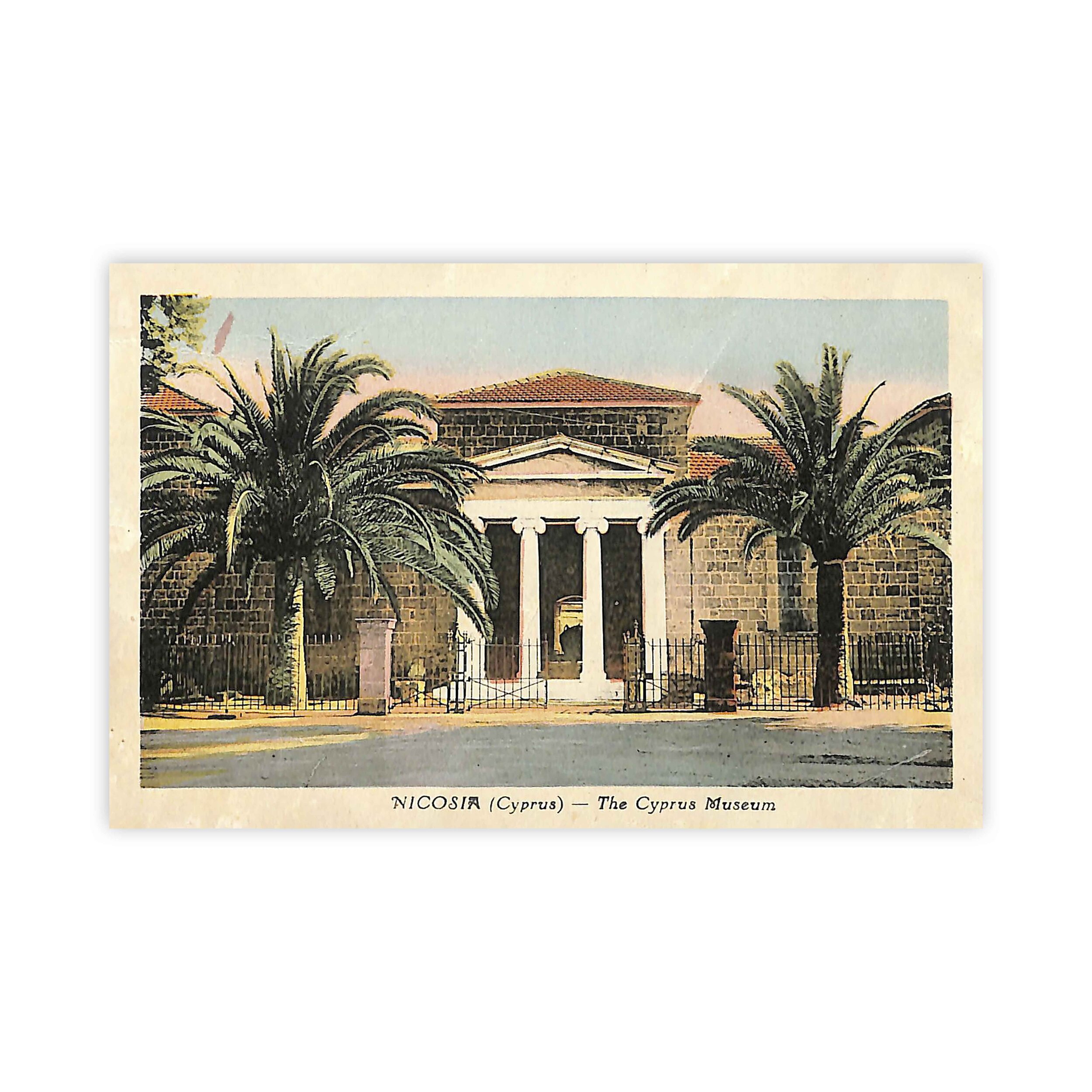

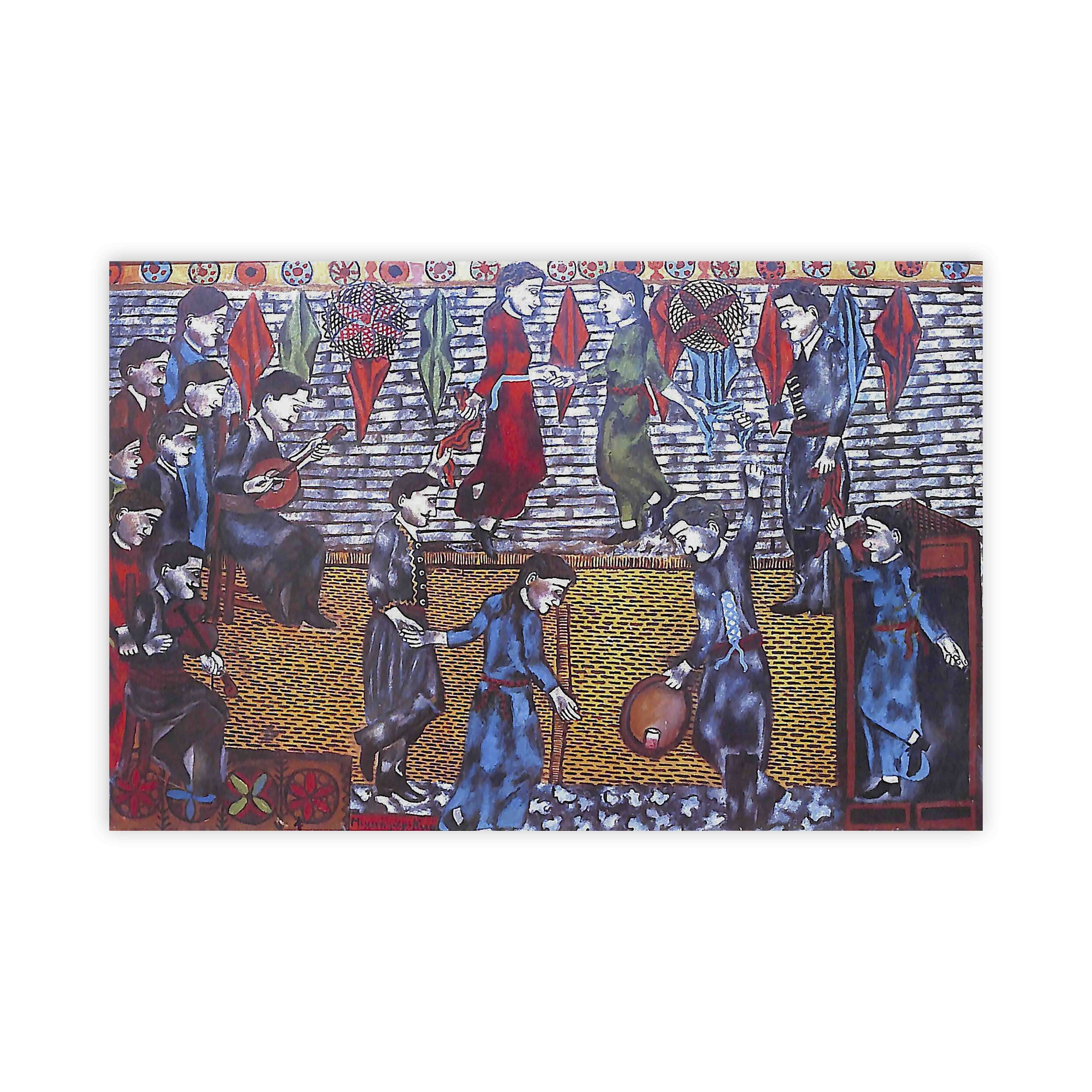

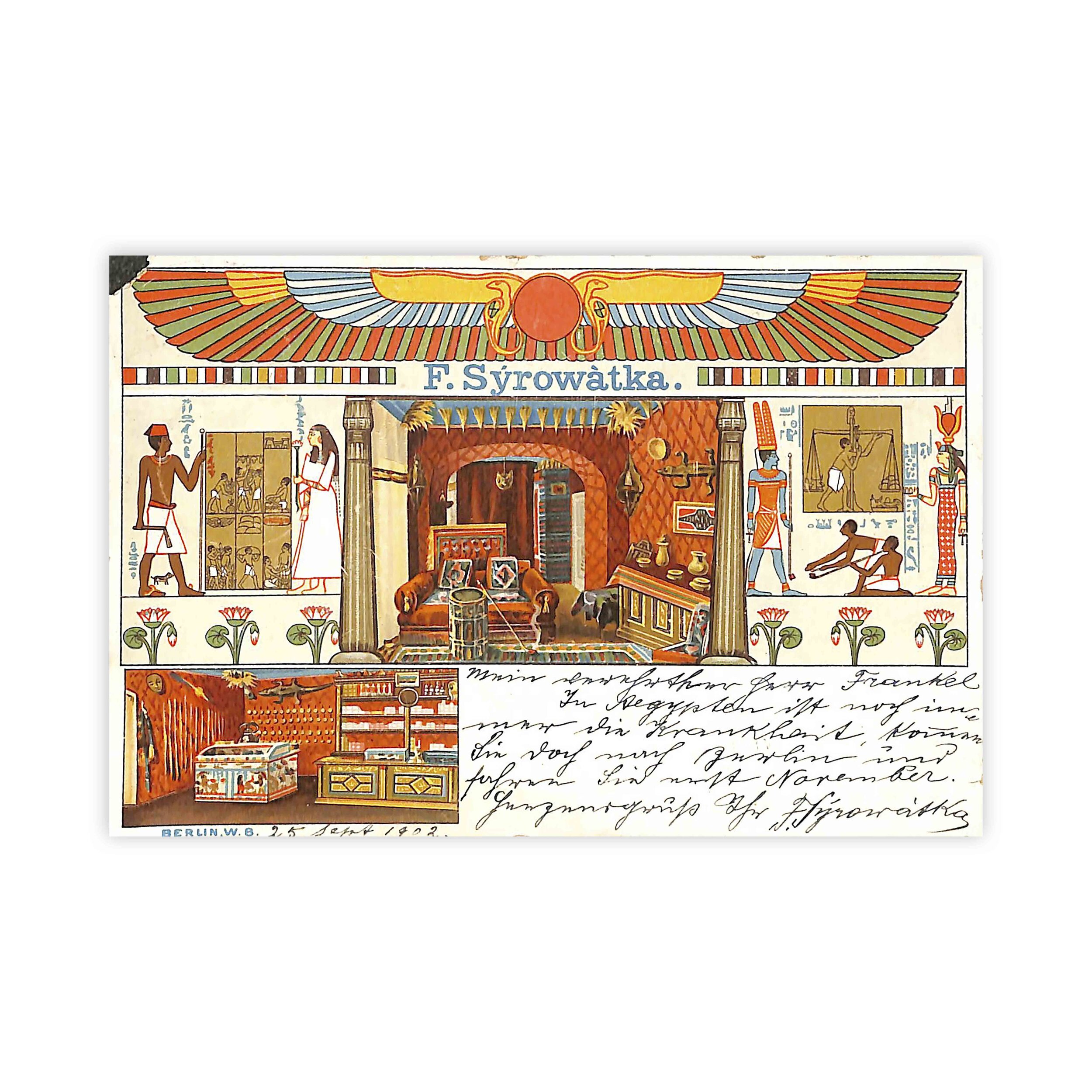

“I’ve made you a palm-tree” locates historically the seed’s arrival to the island of Cyprus, emphasizing its connection to the person that planted it and lived with it. A tall and sturdy column rooted into soil, defying the horizon with its vertical outreach, opening up towards the sky into an ‘eruption’ of long and sharp needle-like leaves. Employing a multidisciplinary approach, the palm-tree is presented an emblem of mobility and displacement of cultural ideals within an open field of chronological and geographical origin. From the relations of the ancient kingdom of Kition to the Phoenicians, the island’s connection to Egypt and the region of Mesopotamia, the rise of the Ottoman Empire, to the modernization of costal fronts according to international trade models. The seed's travel and spread presents itself through diverse perspectives of spatial placement or social perception, exploring the sense of 'belonging' in relation to current sociopolitical conditions. Through the practice of photography, installation, graphic design and writing, the human body, as primary material for creation, is ‘planted’ in parallel to the palm-tree, as a symbol that appears to be local and familiar, simultaneously foreign and exotic.

…in as much as we are a plant not of an earthly but of a heavenly growth, raises us from earth to our kindred who are in heaven. And in this we say truly; for the divine power suspended the head and root of us from that place where the generation of the soul first began, and thus made the whole body upright. - Plato, Timaeus, 90 a-b

What is the nature of a human being and who is the human being in nature, which nature. In Greek, the word human (άνθρωπος - anthropos) denotes the being that is able to move upwards. Trees have the same tendency. Usually, one nourishes the other, both nourished by the soil and the sky, grow and bear fruit, and in the end, die. What is the difference between the two and what condition defines their relation. To which degree the tree becomes humanized and how much of a tree can a human become.

Physical and symbolic dimensions often combine, giving birth to monsters, hybrids like the man-eating trees of the Alps, the oracle trees, the “Homo arbor inversa” of Renaissance, the Mandragora of alchemists and of Machiavelli, Daphne and Narcissus. Fruits of the mind’s imagination, the language of symbols provides endless lists of trees and plants that mean one or the other, according to time and place.

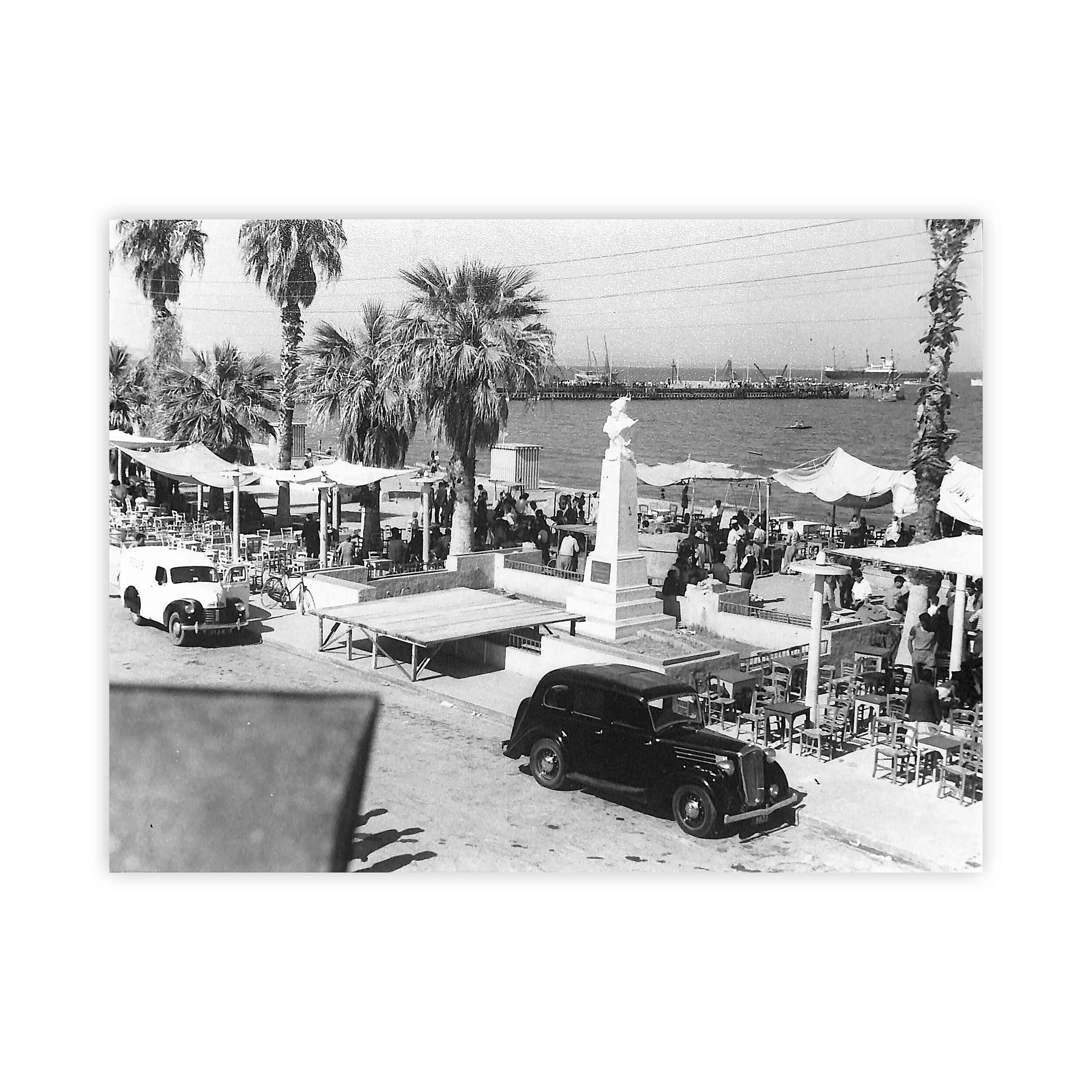

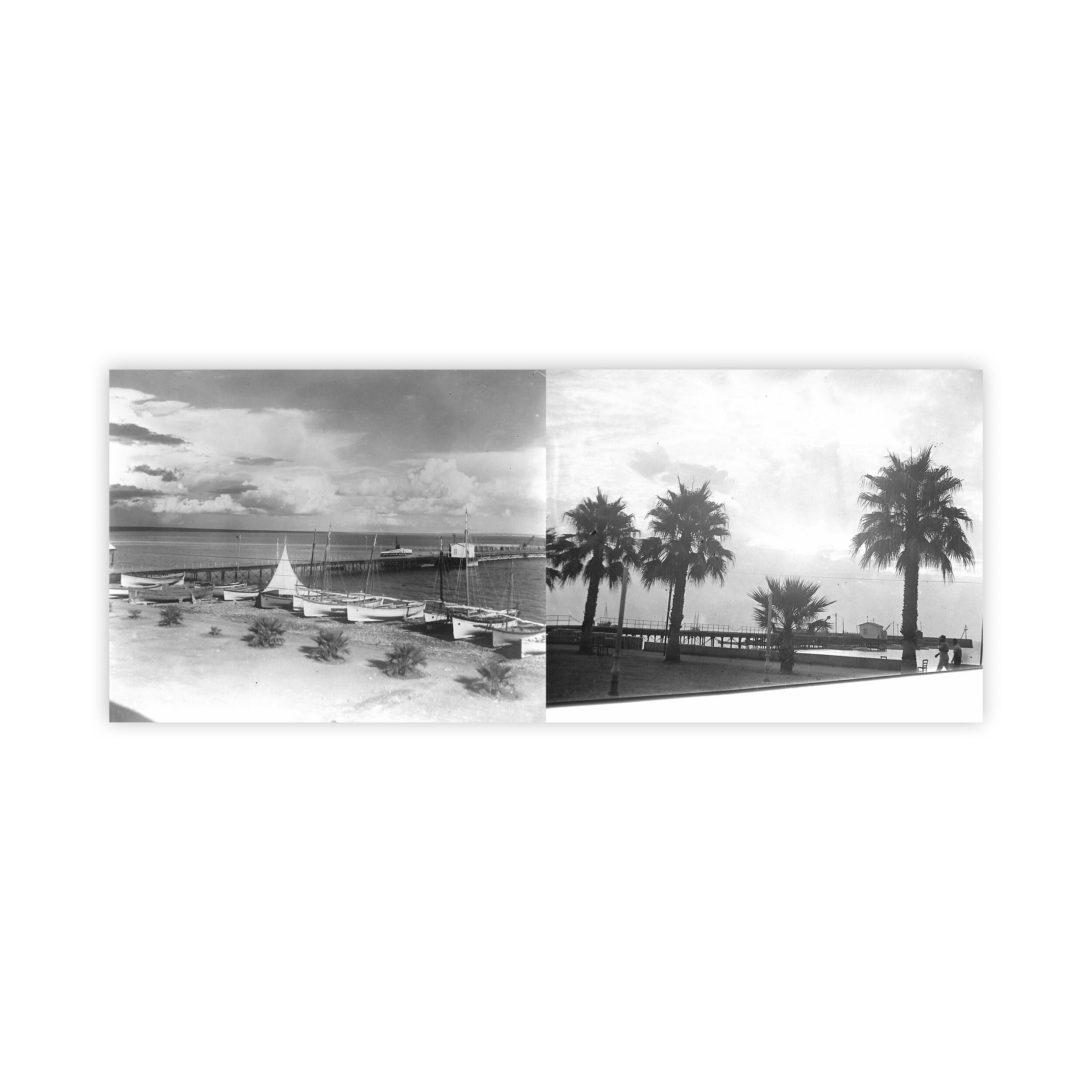

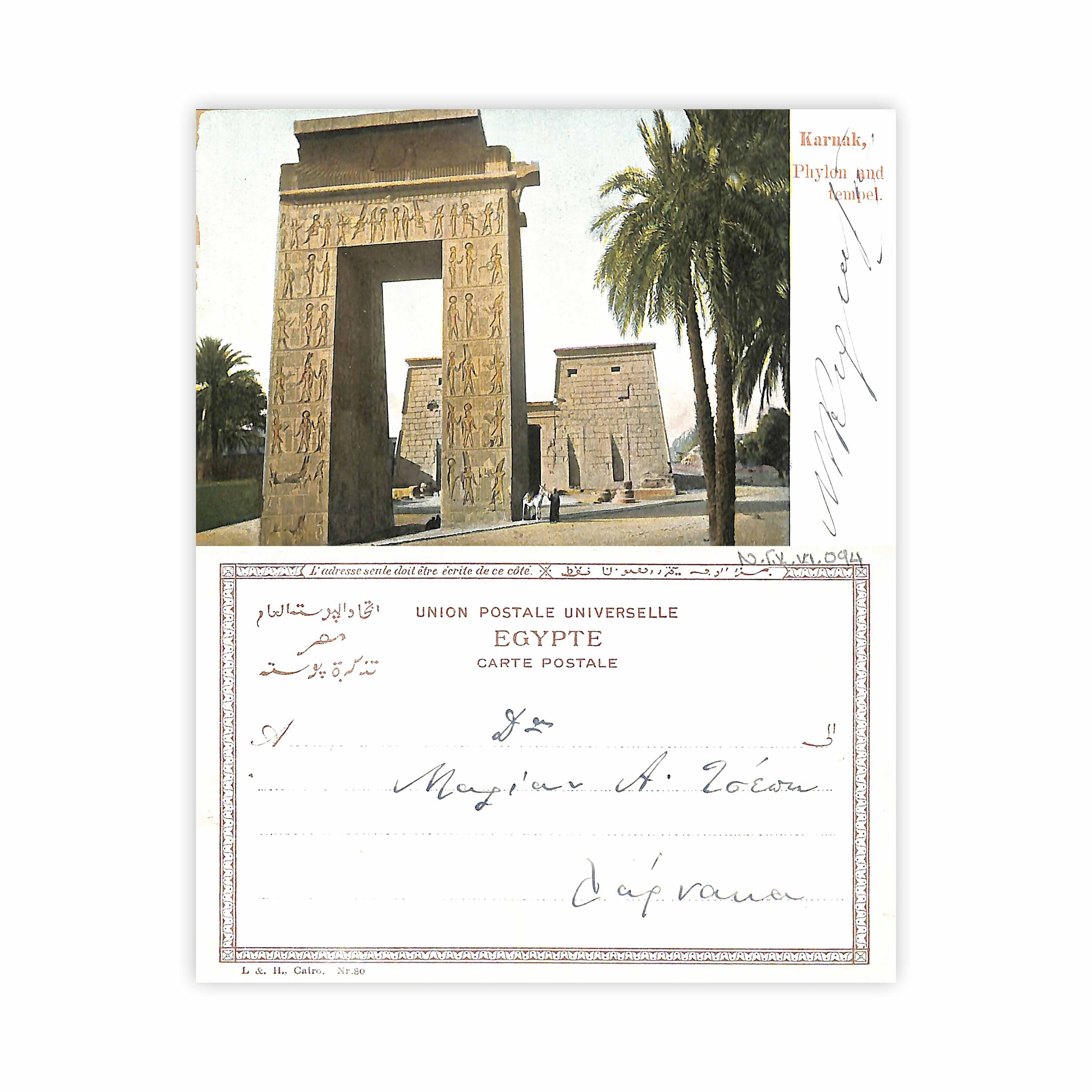

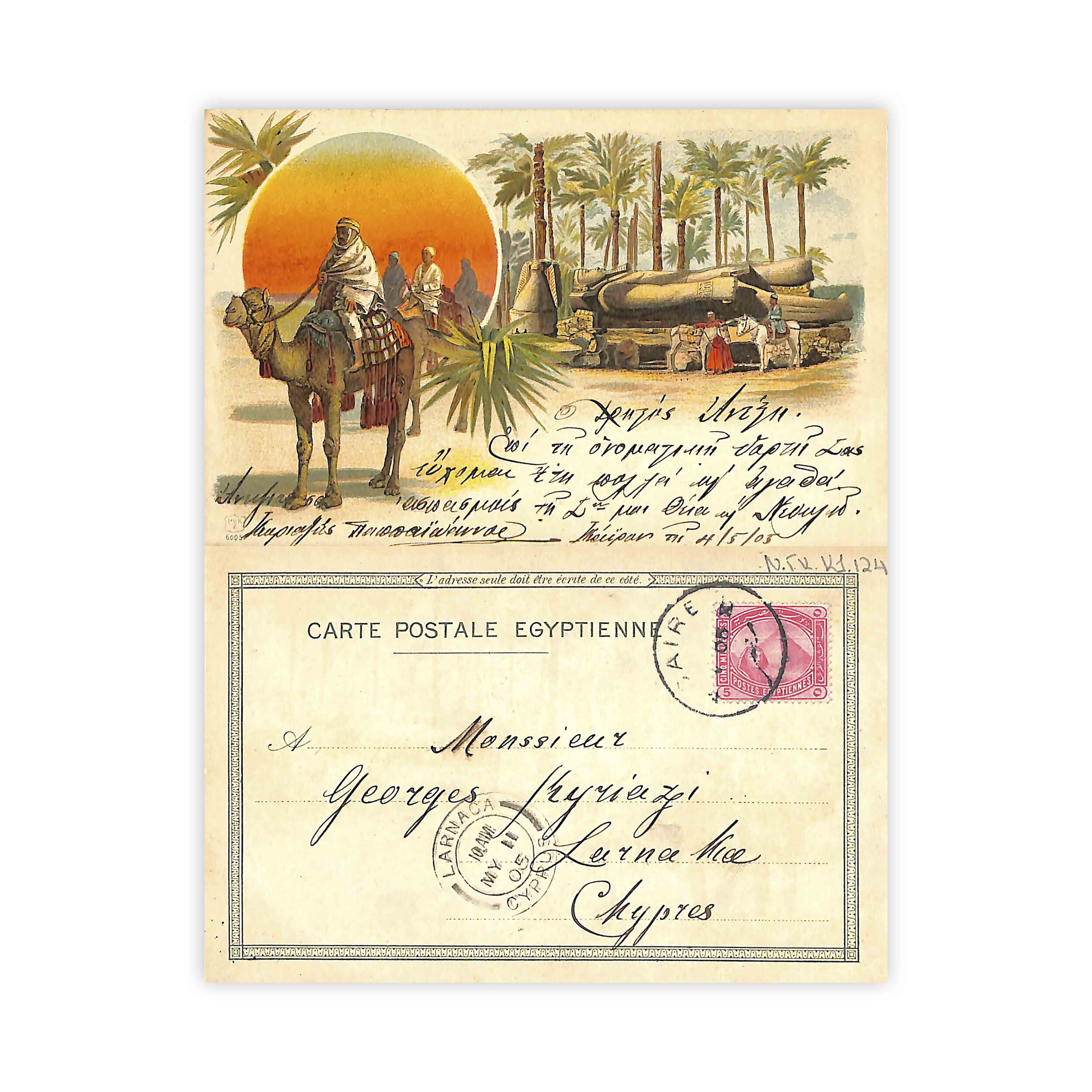

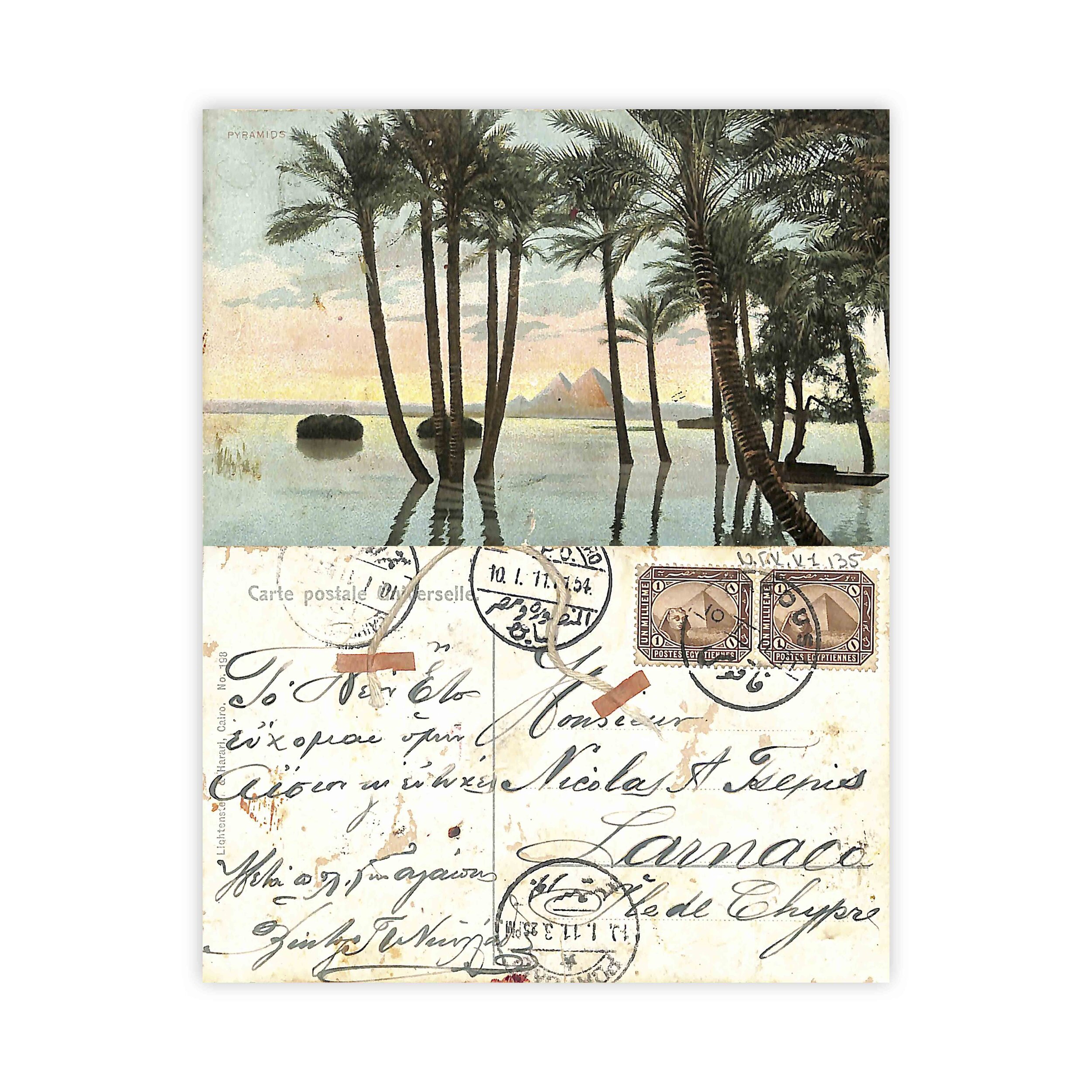

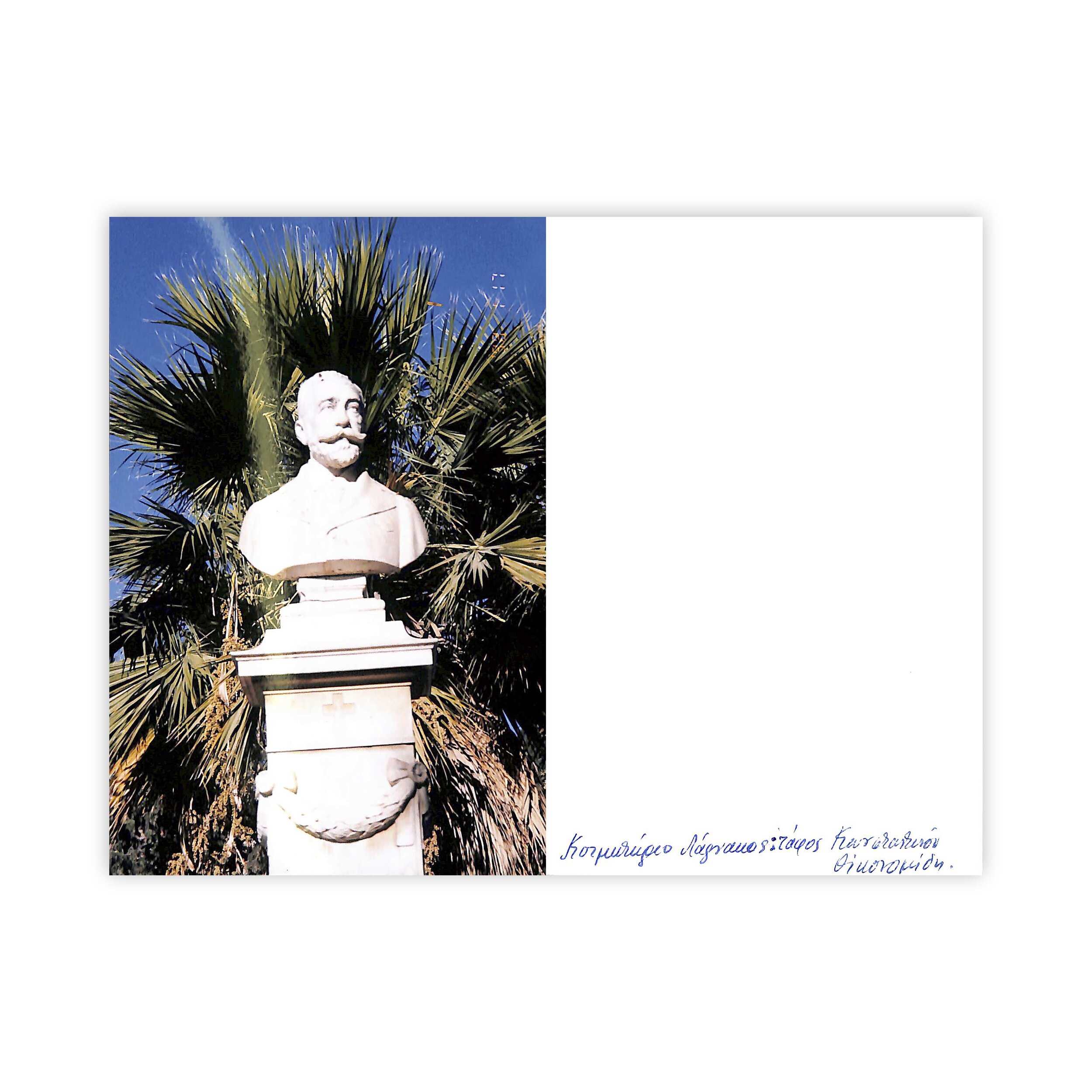

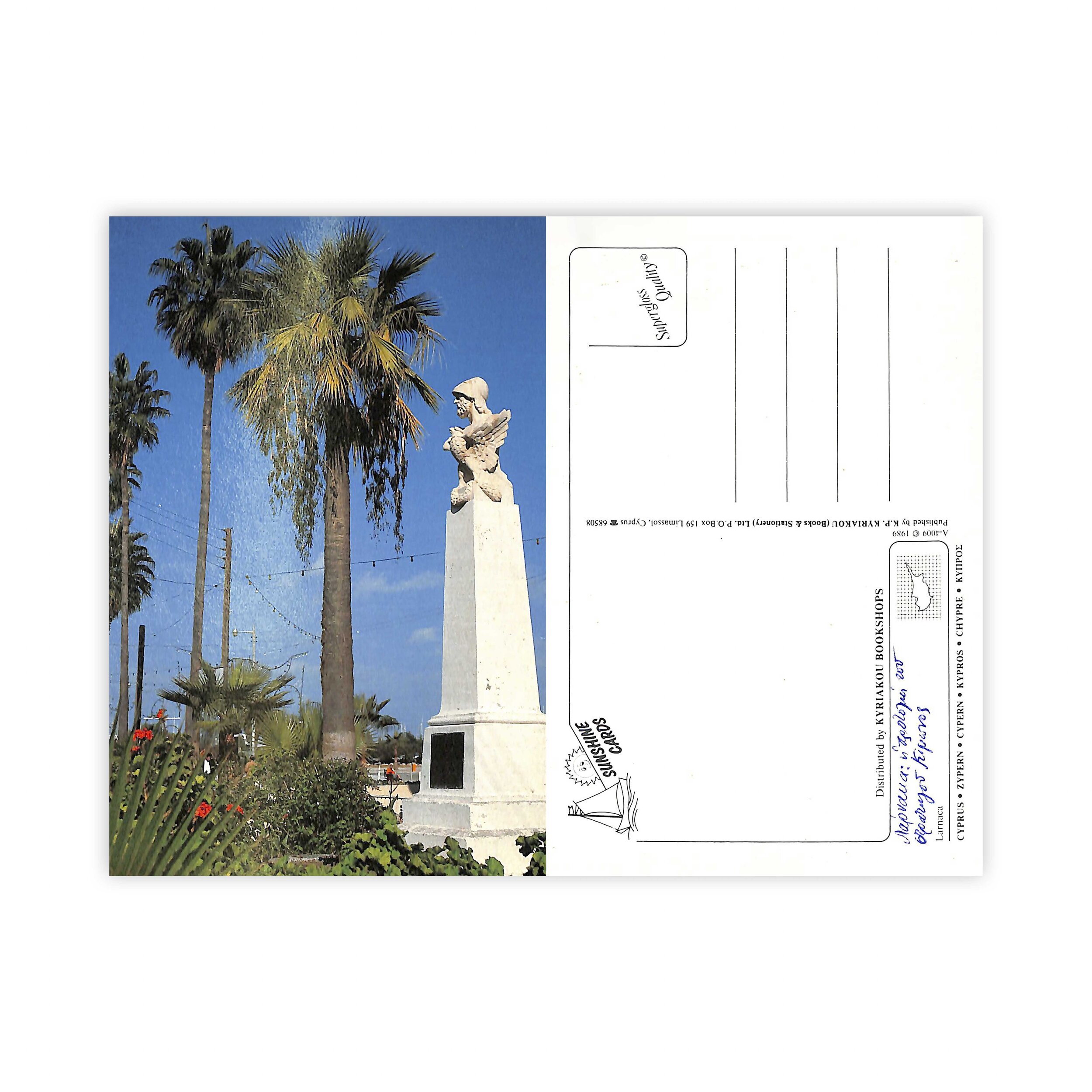

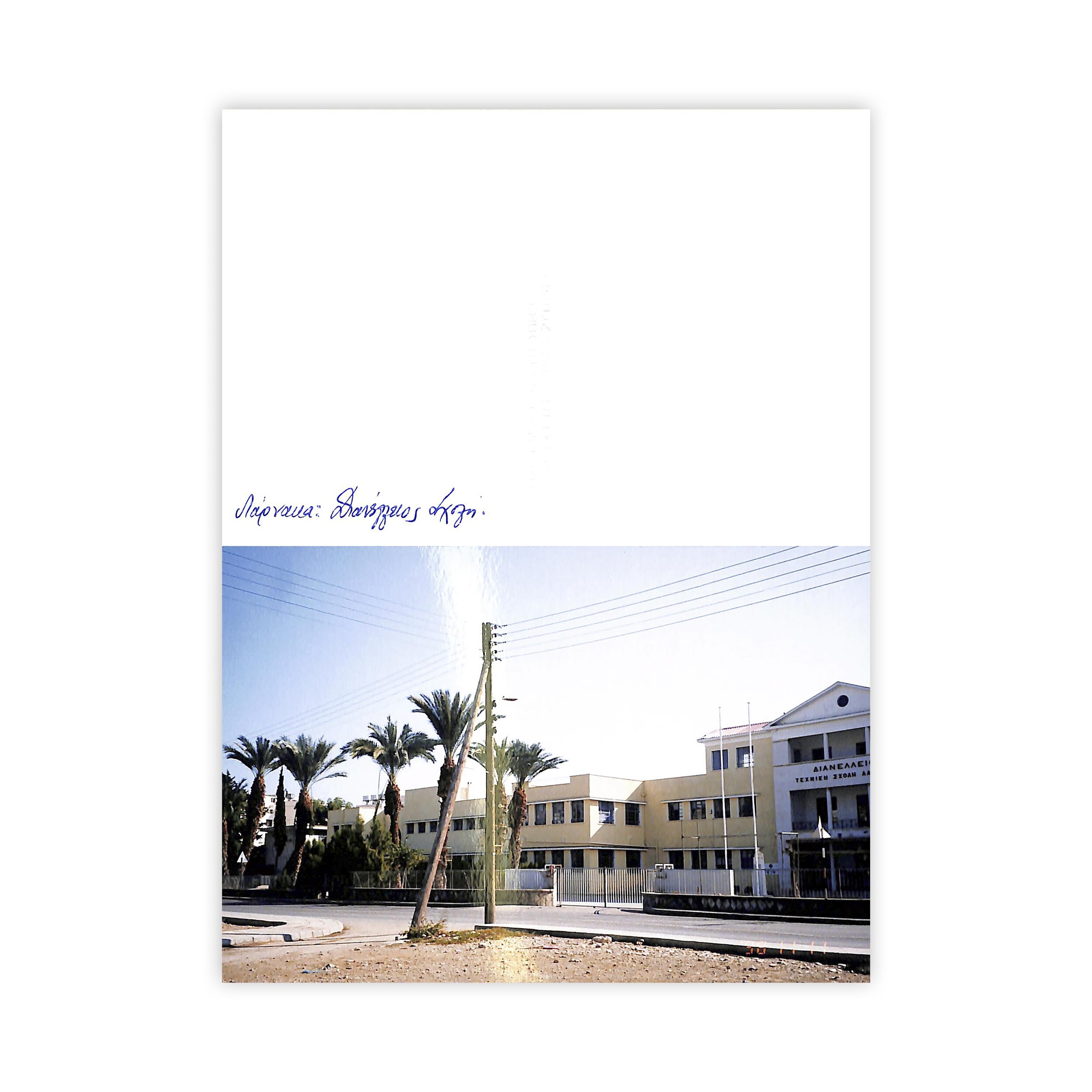

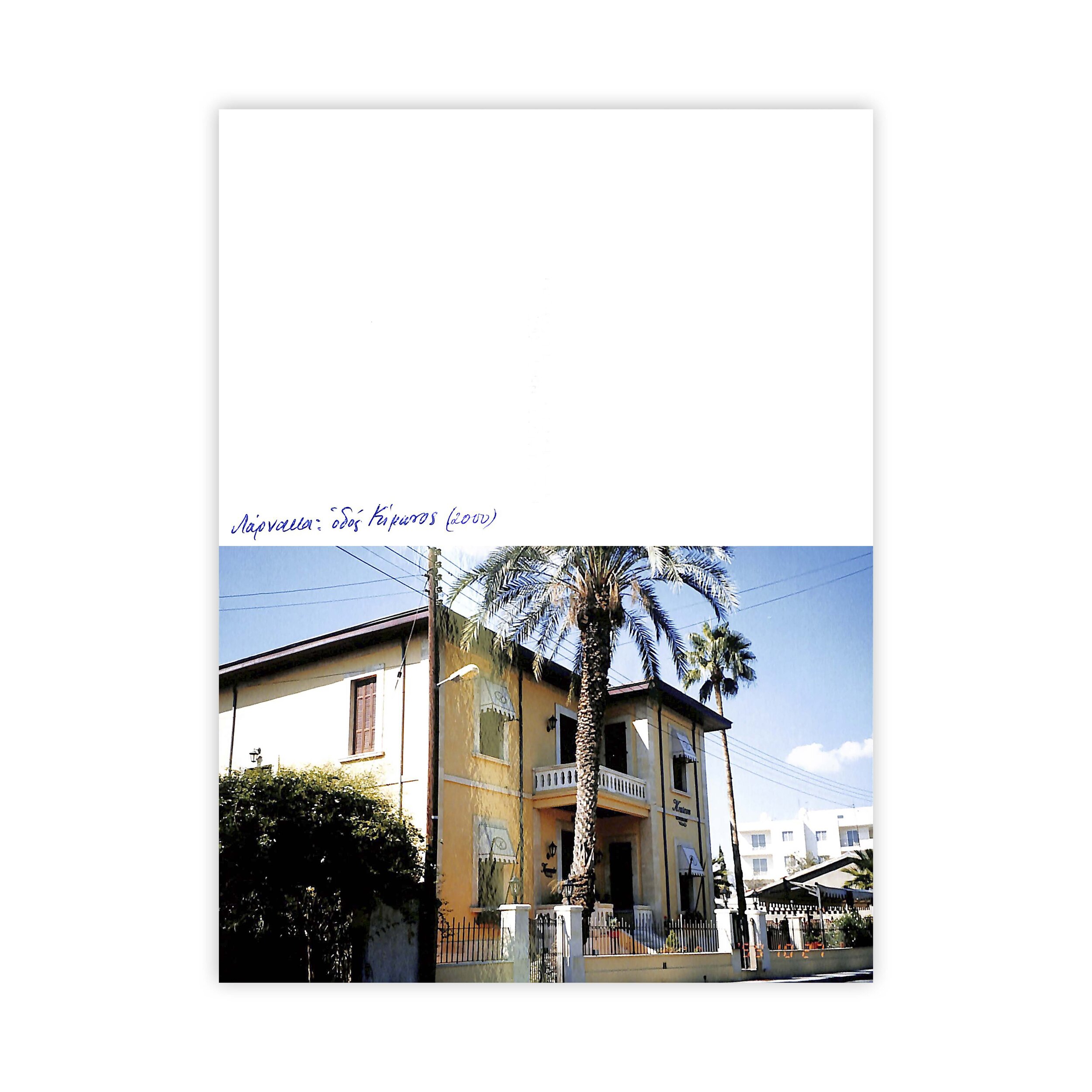

Through archival research, PASHIAS explores the presence of the palm-tree in the geographical and social setting of Cyprus, documenting the values and conditions that characterize it. Building up the material housed at the Phivos Stavrides Foundation - Larnaca Archives, the researcher collected black and white memories on yellow paper, postcards combining landscapes from Egypt and Cyprus, posters and touristic advertisements, images, objects, phrases and customs that charged the artist until he transformed into a pareidolia of the tree.

Exotic and yet so local, the palm-tree characterizes mainly the urban landscapes of the island and states an identity that many of us would refuse. It screams about the East and explodes like a frozen green firework. Brought to Cyprus by the Phoenicians; Phoenicians and palm-trees (φοίνικες - phoinikes) in the city of Kition that became the 20th century’s Larnaca by importing their exotic transatlantic sisters from Côte d'Azur. Leaves like fingers and leaves like palms, lick the sky and determine the tempo of our daily routine. A compliment places us at the top and we often live with the hope of never falling off. Unintentionally, the tree was connected with social uplift, the applause of the many. Its peak became the Ithaca of our vanity and its trunk transformed into the prison of our expectations.

The human - palm - tree gets trapped in its effort to grow, stands still, buried in the soil, part of the urban landscape in an unspecified area, a yard of another era conquered by private transport vehicles. These constitute small palm-trees, since through them we measure our social status. Cars are our mobile private spaces; through them we are called to watch a happening. After all, this is how we are accustomed to experience nature, through our vehicles, similar to snails or turtles. And because the human has an upwards tendency, he can’t be removed from his explosive Ego. Planted in earth, he continues to protest, asking for help in his situation, and in ours. Releasing a smoke bomb in order to reach the palm’s mane, he asks of the wind to bring a prophecy blowing favorably to the right. Thus, he becomes the mute scream of the captive social being, an emblem for the human who wants to be and to be seen, in order to balance upon the limits of the social horizon.

The palm - tree becomes fashion and runs across all costal fronts and hotels, it becomes an identity and colours the domestic yards in which it keeps growing. The palm - human becomes the concept and method of PASHIAS’ expressive design and presents itself as a visual performance artwork, elsewhere as an intervention - exhibition, continuing in more facets through time and space.

Dr. Iosif Hadjikyriakos - Head of Phivos Stavrides Foundation

“Crowning”, Digital Photography, Venetian Walls - Nicosia, PASHIAS, 2020.

“Protaras”, Digital Photography, Protaras - Paralimni, PASHIAS, 2020.

“I’ve made you a palm-tree”, Digital Design, Katerina Scoufaridou, 2020.

So too you have palm-trees, the tallest in the world, but they do not (as some fancy) bring their fruit to maturity, like those of upper Africa, Arabia, Felix and Egypt. I never saw any, nor can they ripen there any more than in Crete, Rhodes or the Mediterranean islands generally. I say this, because I know that many persons have fallen into error, and have mistakenly written that these palm-trees produce very good fruit which we call dates.

- Thevet, 1556

The city is rich in gardens full chiefly of date palms: the number of crows is incredible, the trees are black with them: they are useful as an alarum, for at dawn their croaking makes it impossible to sleep.

- Stochove, 1631

The other houses in the city inhabited by the Turks are generally of good cut stone, built, we were told, by the Venetians, and the streets are wide and handsome. The houses are set in beautiful gardens, well planted, chiefly with the palms which bear dates.

- Hurtrel, 1670

The palm-trees which are thinly scattered about the back of the town give it a very Egyptian appearance, and I am told make it very much resemble Alexandria.

- Frankland, 1827

The palm-tree abounds in Nicosia and Lefca, and is also found in smaller numbers in Larnaca and Limasol. Its presence in a village generally indicates that the majority of the inhabitants are Turks, the Mussulmans being much attached to this tree. The dates produced by the Cyprian Palms are much inferior to those of Egypt, and never attain the same degree of maturity.

- Savile, 1878

At the side of the relic another stone represents a man holding a palm-branch, perhaps to indicate that he is the victor in one of the public games or in the circus.

- Palma Di Cesnola, 1882